Today we look back at Théâtre National de Bretagne’s unusual production of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. We at CatSynth had the opportunity to see it at Zellerbach Hall in Berkeley, California a couple of weeks ago.

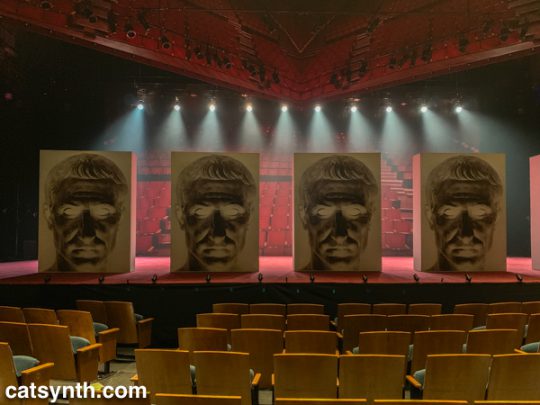

It is a play we know well, having read the original and recently revisited Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s epic 1953 film version starring Marlon Brando, James Mason, and John Gielgud. In contrast to that version which places the play in a grand realization of ancient Rome with large sets and hundreds of extras, this production directed by Arthur Nauzyciel with set design Scott Zielinski, was abstract and spare: a mostly empty stage surrounded by a backdrop of empty theater seats. The cast was stripped down to a small set of players, some pulling multiple roles – both Portia and Calpurnia were played by Sara Kathryn Bakker, for example. Their costumes (by James Schuette) were inspired by the 1960s, as were the furniture. We see the characters as mostly upper-class individuals in suits and dresses in spare rooms with modernist furniture, something directly out of Mad Men. We first see Brutus (James Waterson), Cassius (Mark Montgomery), and Julius Caesar (Dylan Kyussman) in simple tuxedos, with Mark Antony (Daniel Pettrow) bounding in wearing an Adidas tracksuit – a nice touch that harkened back to Brando’s jockish first scene as Antony in the 1953 film. One cannot consider these things anachronistic, seeing as how the Shakespeare play in itself is an anachronism, with its mentioning of clocks, doublets, etc., not to leave out the fact that it was written and generally performed in English. The drama is what is most important in the play, the interaction of the characters, and the mechanics of politics and public opinion.

Theatre is fundamentally about illusion and representation. Sometimes, perhaps most of the time, in older forms of theatre, minimalism accentuates the essence of what a dramatic piece is trying to convey. All of the information is conveyed through the words and actions, with the dressing secondary. As I believe it should be with Shakespeare. So I felt the right tone was taken with the way the visual aspect was handled.

Of course, the central element of such a play is the acting and interpretation of the text. Kyussman’s portrayal of Caesar brought the right mixture of pomp and gravitas to his character. Waterson’s Brutus came across as conflicted in his feelings, ultimately choosing reason over loyalty. And Montgomery’s Cassius was a thoughtful but odd fellow. Bakker’s double-duty as Portia and Calpurnia was beautifully played but also served to highlight the overall lack of women characters in the play. Something I was ambivalent about was the decision to excise the scene with Cinna the Poet, and his being swept up by the angry mob and killed, having been confused with Cinna of the conspirators. This scene is excised from many stage productions and most films of the play, for purposes of pacing, which is unfortunate. I feel it is a crucial scene which shows the madness of crowds, the way opinio publica can be twisted by those who seek to further their own ends = “The abuse of greatness is when it disjoins remorse from power”, indeed.

The lighting was also a major player in this production. For most of the early scenes, the stage was shrouded in a mixture of darkness and low lighting. It is only when we get to the Capitol and the chamber of the Senate that the lights become bright, drawing us to a very stylized and choreographed assassination of Caesar. This continues into the speeches of Brutus and Antony before changing again into an eerie fog-filled atmosphere for the war scenes of the final act.

Perhaps the most unusual aspect of this production was the use of a live jazz trio, who performed between acts, and occasionally between scenes. The musicians (Marianne Solivan on vocals, Dmitry Ishenko on bass, and Leandro Pelligrino on guitar) were all top-notch and performed extremely well. But we were anticipating original music. What was presented was a selection of standards. In itself, this was not disappointing – and the joining in by Bakker as Portia and Montgomery as Cassius was fun. However, the selection of pieces – which, lyrically, commented upon the action with a winking, postmodern irony – in some ways undercut the otherwise serious and austere quality of the production and interpretation of the play. After the scene between Brutus and Portia, we were given “You’ve Changed”. In the entr’acte, we heard “Is That All There Is?” I felt by the end of the performance, it had become something close to a parody.

This sense that the music played against the other dimensions was highlighted in the final song-and-dance number, set to some recently recorded, faceless, autotuned pop song (I’m pretty sure it was a Lady Gaga song, but I can’t confirm). It really seemed to be negating much of what I feel is at the core of this play, very serious ideas about morality, duty, and civic responsibility.

This may be the director’s intention, I don’t know for sure, and I can’t say. The director took many chances with the production and created a fairly unique take on a work which has been performed so many times, in different ways. “How many ages hence shall this, our lofty scene, be acted over in states unborn and accents yet unknown”, indeed.

Overall we enjoyed the performance, the design, and the acting. And I like to see productions of Shakespeare’s plays take chances with new directions rather than simply redoing the same thing over and over again. But with any experiment, sometimes things work and sometimes things do not. The end result here was mixed and ambiguous. But perhaps that was the point.

[Jason Berry contributed to this review.]