We pick up our report from our recent visit to the Museum of Modern in Art where we left off after Part 1. Working my way gradually downstairs, I came to the special exhibition Sur moderno: Journeys of Abstraction―The Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Gift. This is a major exhibition that fills several galleries with modernist works by South American artists through the 20th century.

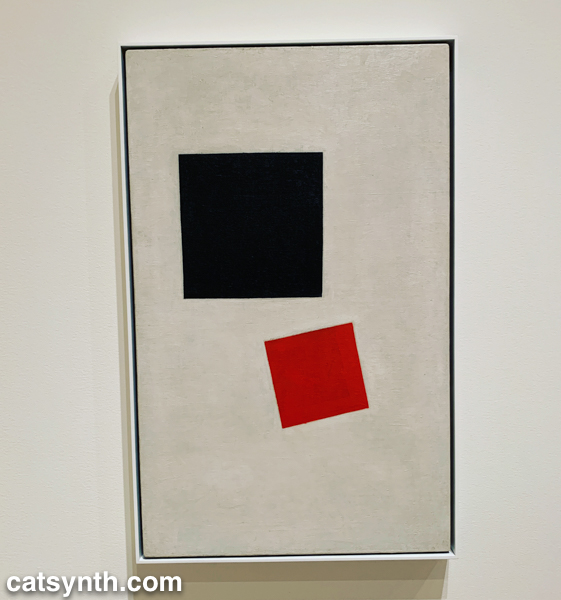

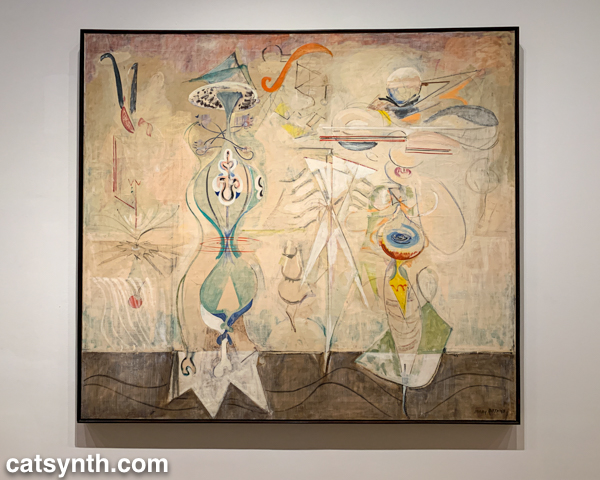

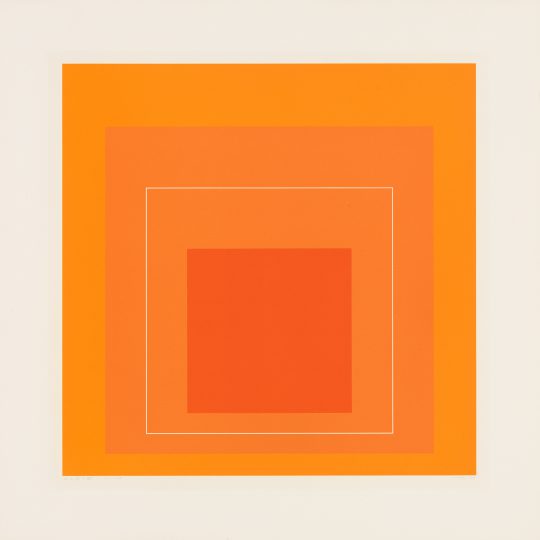

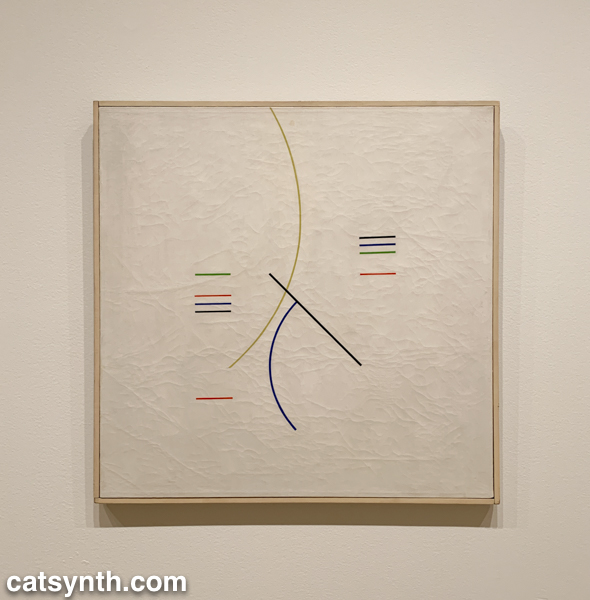

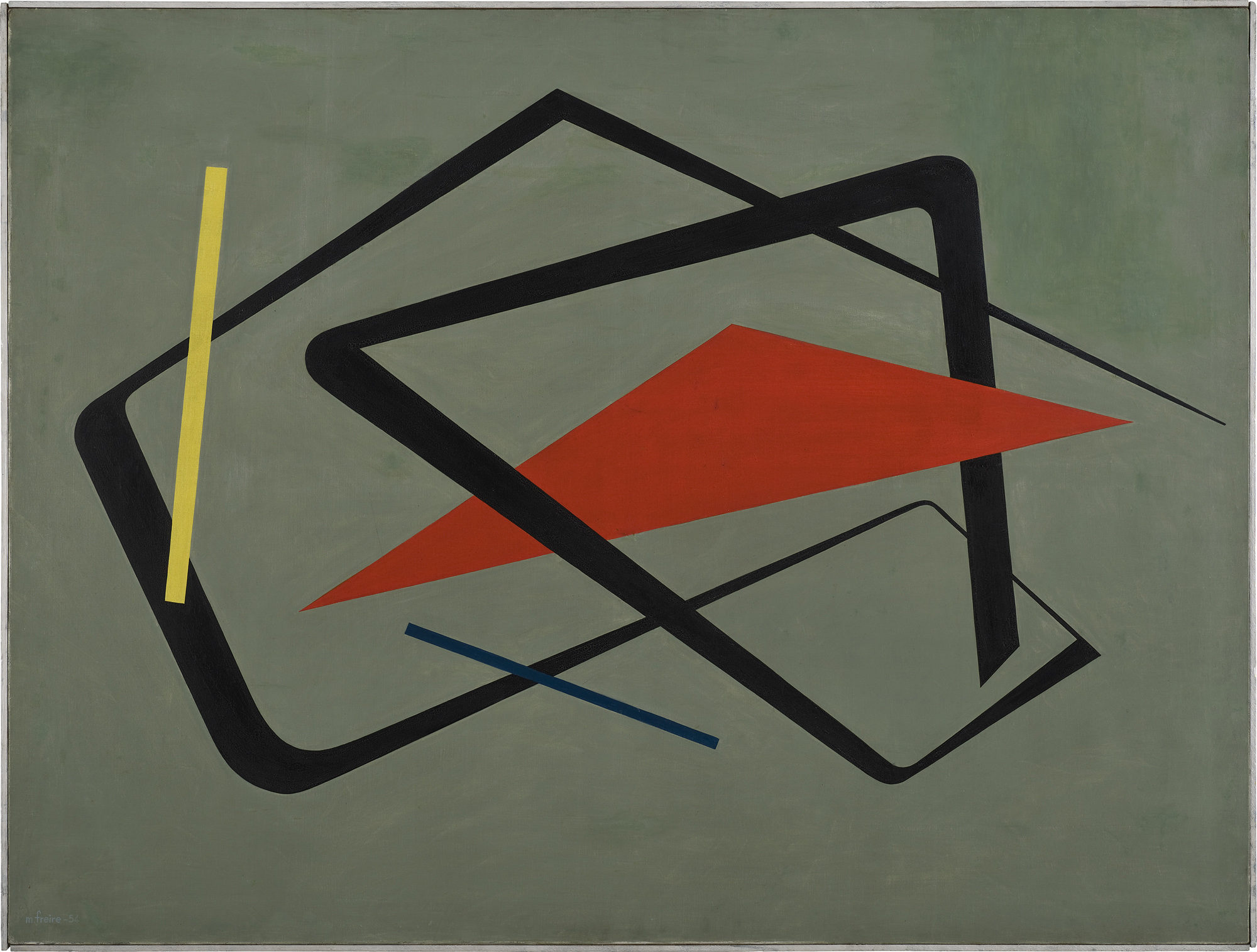

As in other parts of the world, South American artists embraced abstraction in the decades following World War II, with lines shapes of minimal color palettes. In his aptly named Curves and Straight Series, Argentine artist Alfredo Hlito takes this to an extreme with thin lines and curves against an off-white background, while Uruguayan artist María Friere used bolder lines and colors in her Untitled.

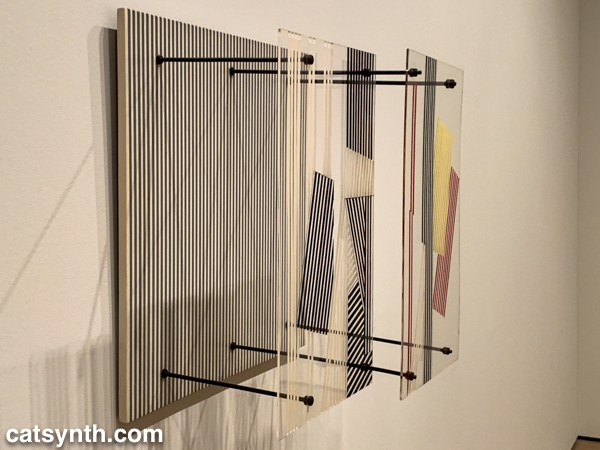

Both of these pieces feel like they could have been three-dimensional pieces of design, and in fact, the exhibition does include several striking three-dimensional works. When seen head-on, Jesús Rafael Soto’s Double Transparency appears to be a plat painting or print, but from the side the depth becomes apparent.

Jesús Rafael Soto. Double Transparency / Doble transparencia, 1956 . Oil on plexiglass and wood with metal rods and bolts. 21 5/8 × 21 5/8 × 12 5/8″ (55 × 55 × 32 cm)

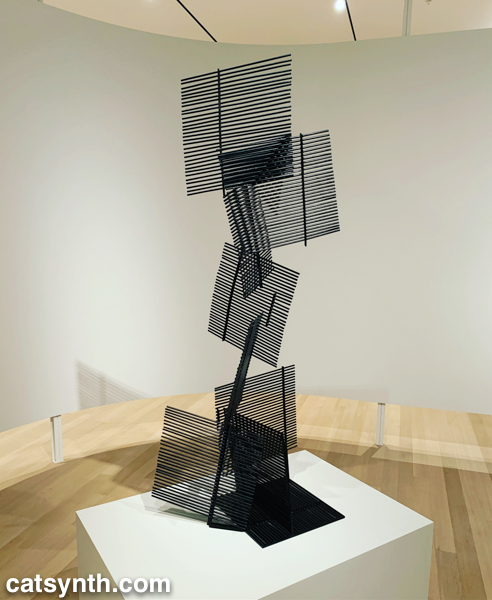

The lines-in-space motif is also used in Ocho cuadrados (Eight Squares) by Gertrud Goldschmidt, also known as Gego.

The recurring motifs in many of the works show the influence of Piet Mondrian, not just the most familiar neoplastic pieces but his earlier and later work as well. Indeed, I was happy to find Broadway Boogie Woogie hanging in this exhibition after not seeing it in the main collection display. As much as any work in MoMA’s permanent collection, I have a regard for this painting as if it were a friend and not just a work of art.

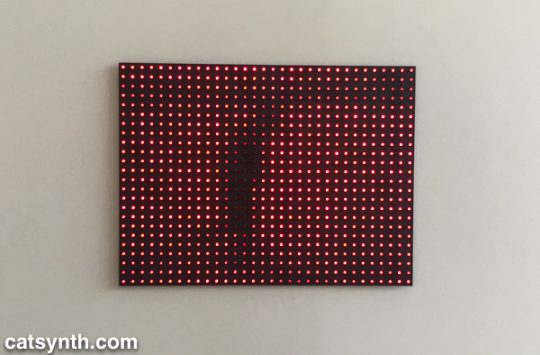

But perhaps the most extreme interpretation of the grid was found in Antonieta Sosa’s Visual Chess.

37 1/8 × 37 1/16 × 1 3/16″ (94.3 × 94.2 × 3 cm)

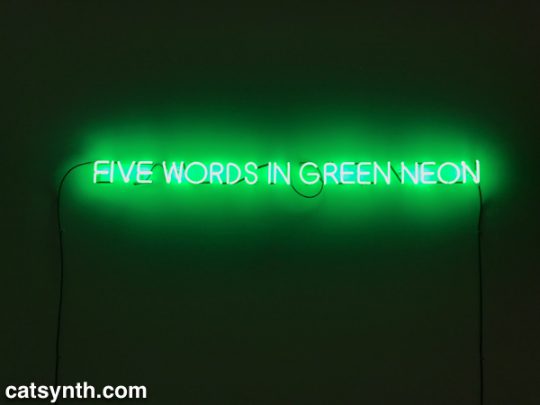

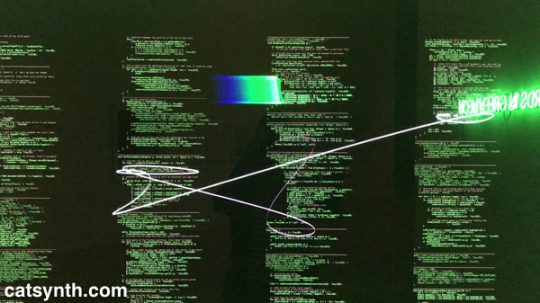

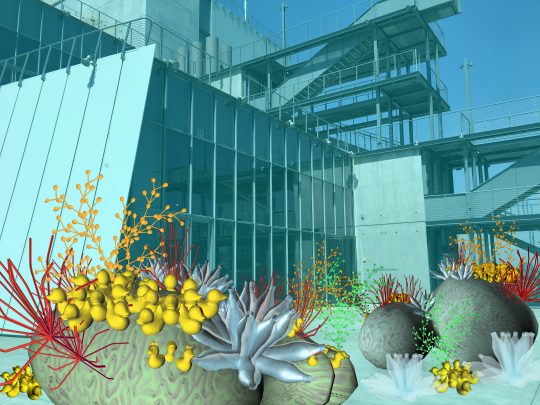

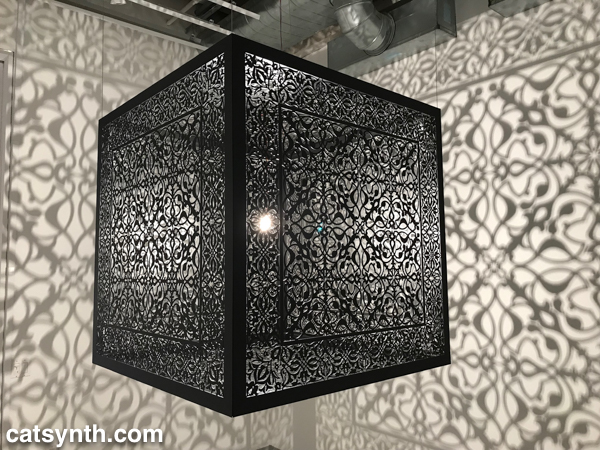

As part of its expansion, MoMA launched a new gallery space called the Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Studio, or simply “the Studio”, a space dedicated for live, interactive, and multimedia art. The inaugural exhibit was Rainforest V, an evolution of David Tudor’s Rainforest. Originally a score for a collaboration with Merce Cunningham, it evolved into a performance installation. The latest version, realized by Composers Inside Electronics (CIE), is controlled by computer rather than live performers, as visitors wander through the space.

The installation is constructed from everyday objects, such as a metal barrel, a vintage computer hard disc, plastic tubing, wood crates, and more. The objects and materials are fitted with a vast array of speakers and become resonators that shape and amplify the sound.

The best moments are getting close to an object, such as the barrel or balsa-wood box with simulated earphones, and standing for a moment then walking around. I regret that an iPhone in a crowded gallery is not the best way to record and share it with readers – it really music be seen in person.

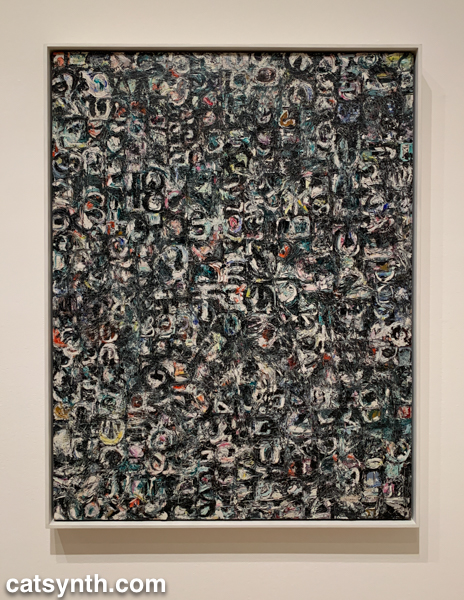

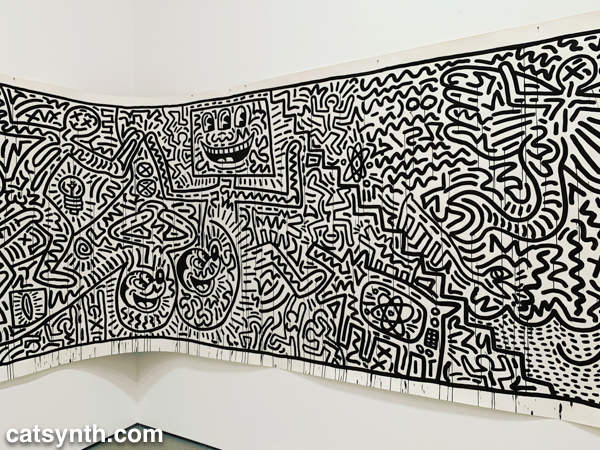

There was still more to see, including the newly expanded second-floor gallery for contemporary (1980s-present) works. This period has traditionally been a more mixed one for me, but there are gems and inspirations to be found. There was a large gallery-spanning work by Keith Haring.

An equally monumental piece by Julie Mehretu called Empirical Construction: Istanbul a fantastic futuristic cityscape radiating in multiple dimensions.

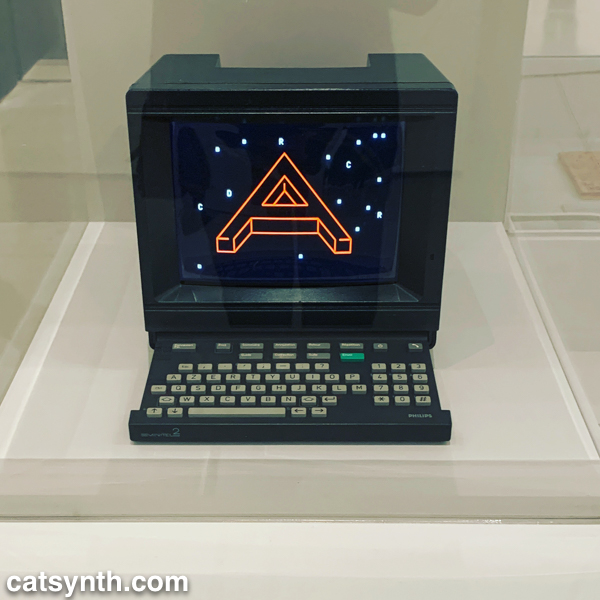

On the opposite scale is Eduardo Kac’s Reabracadabra, a video piece realized as graphics inside a vintage Minitel terminal.

Kac’s piece reminded me of my interest in vintage electronics finding new life as dynamic art pieces.

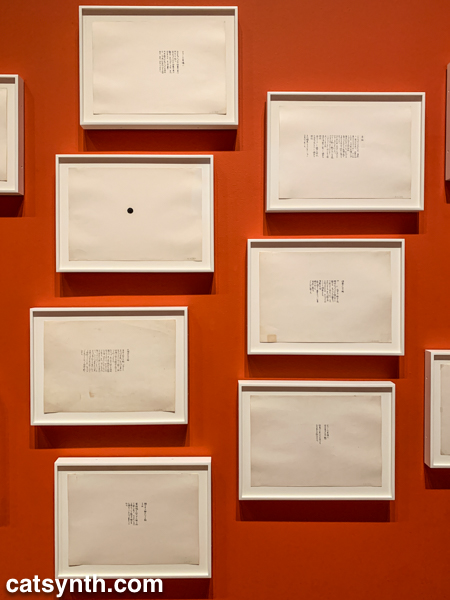

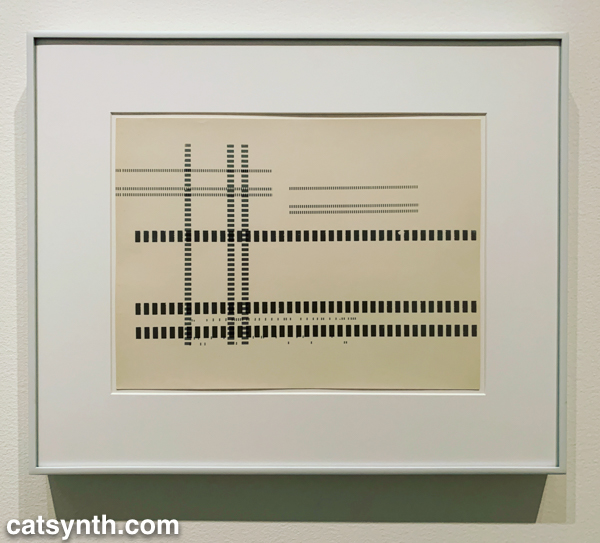

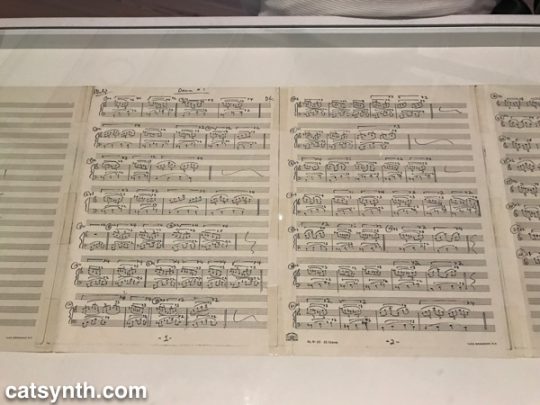

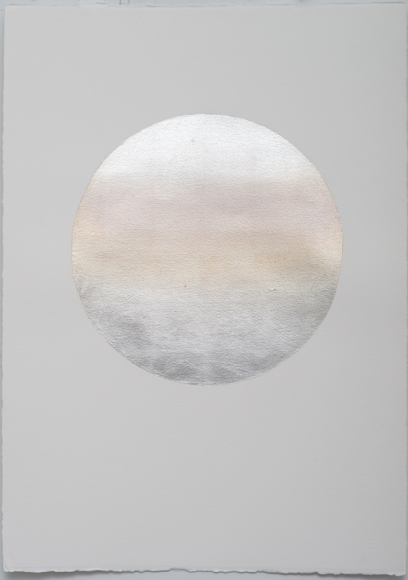

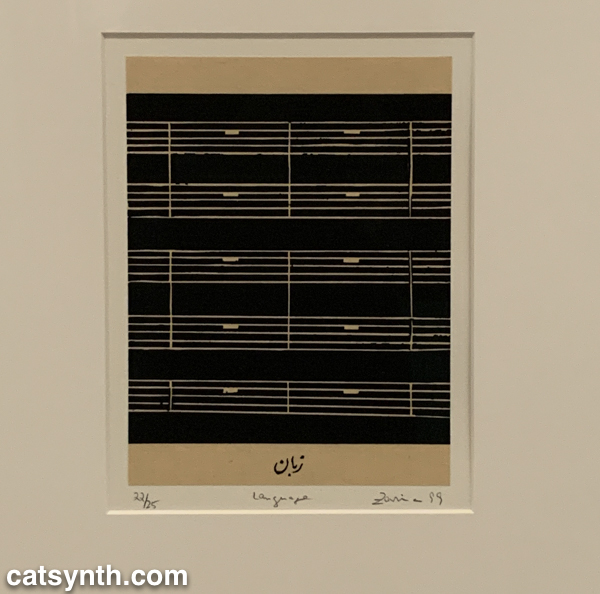

We end with one panel from a larger work by the artist Zarina, Home Is A Foreign Place.

There is something bleak about an entire musical score made of rests, but also intriguing, and even curious. It is perhaps a reminder that exploring a museum top to bottom invites one to escape one’s comfort zones even at the same time as seeking comfort and solace. I’m glad this visit afforded opportunities for both.