Facebook has been in the news quite a lot of late. None of it for good reasons. But buried amidst the articles on data privacy and the Cambridge Analytica scandal I found the story “Welcome to Zucktown. Where Everything Is Just Zucky.” in The New York Times. Basically, it discusses Facebook’s plans for a new community adjacent to its Menlo Park campus, with housing, shops, and such.

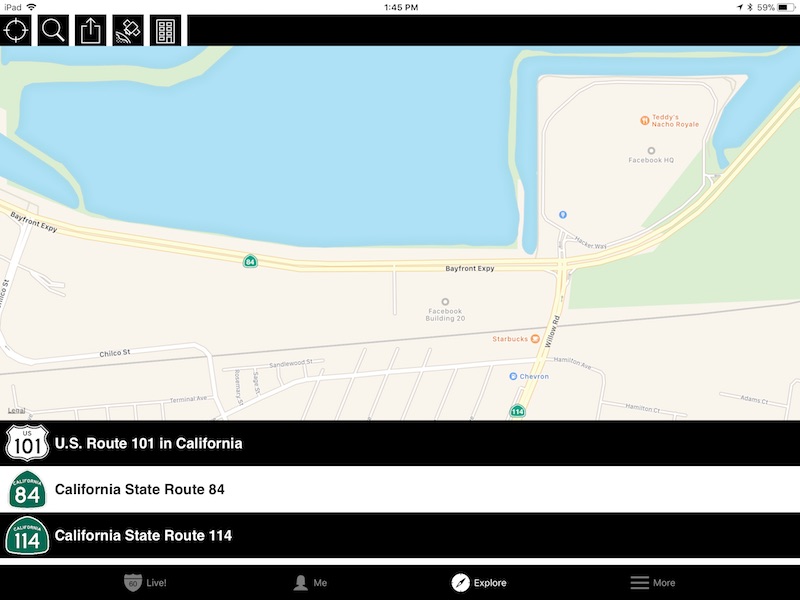

As seen in the above screenshot from our Highway☆ app, Facebook’s campus is at the remote northern edge of Menlo Park, straddling the Bayfront Expressway (California Highway 84). Even by the standards of sprawling Silicon Valley campuses, this one is isolated, with access primarily by car or company busses. The proposed development, which is formally called “Willow Village” (Facebook dislikes the nickname “Zucktown”) would be to its east, between CA 84, Willow Road (unsigned CA 114) and University Avenue (unsigned CA 109), and adjacent to the neighboring town of East Palo Alto. While ostensibly an open community with public access and some affordable housing units, it is clearly being designed for Facebook employees. And although the benefits of living close to work – and cutting down on commutes – are abundant, there is a difference between living near work and living in work. And that is why it touched a raw nerve with me. One of my main critiques working the industry, besides the subtle but rampant sexism, is what I call forced togetherness. In the culture of many tech companies, it isn’t enough to do good work every day or even work long hours. There is tremendous pressure, implicit or explicit, to be socially present at all times, to treat the company as one’s community, one’s “life”.

As seen in the above screenshot from our Highway☆ app, Facebook’s campus is at the remote northern edge of Menlo Park, straddling the Bayfront Expressway (California Highway 84). Even by the standards of sprawling Silicon Valley campuses, this one is isolated, with access primarily by car or company busses. The proposed development, which is formally called “Willow Village” (Facebook dislikes the nickname “Zucktown”) would be to its east, between CA 84, Willow Road (unsigned CA 114) and University Avenue (unsigned CA 109), and adjacent to the neighboring town of East Palo Alto. While ostensibly an open community with public access and some affordable housing units, it is clearly being designed for Facebook employees. And although the benefits of living close to work – and cutting down on commutes – are abundant, there is a difference between living near work and living in work. And that is why it touched a raw nerve with me. One of my main critiques working the industry, besides the subtle but rampant sexism, is what I call forced togetherness. In the culture of many tech companies, it isn’t enough to do good work every day or even work long hours. There is tremendous pressure, implicit or explicit, to be socially present at all times, to treat the company as one’s community, one’s “life”.

Forced togetherness comes in much smaller ways than planned communities of coworkers. At a previous job of mine in 2014 at a tiny startup, everyone ate lunch together almost every day. Ostensibly, it was supposed to be Monday, Wednesday, Friday, but it quickly became clear that Tuesday and Thursday were expected as well. One day early when I politely passed on lunch – and was looking forward to going out by myself for a little bit – the CEO seemed perplexed and kept trying to offer one option after another for ordering lunch in. I had to finally just say “Look, I’m a big girl, I can feed myself!” This was met with some quiet and awkward laughter. It’s not that lunch was mandatory, but there was a social expectation, and implicit coercion, that eating together was the right thing to do.

I have come to look for red flags in this regard. In my current job search, another very small company reached out to me with an interesting opportunity. But they were located in Redwood City. I have more than once stated I would sooner move back to New York than take another job on the peninsula – but I played along and politely explained that I prefer to work in San Francisco proper, but did they have flexible or remote work options. I got the following reply.

We do not do remote. It hinders the culture of the company we are building and we love hanging out with each other.

There are many good reasons that some companies require employees to be on site. But what this message told me was that the policy was based not on a business or practical necessity, but on a virtue, a belief that this is how people should be. It says they are more interested in a culture based on “hanging out with each other” than on “getting things done.” It says that to succeed in that culture, one must be someone that they like to hang out with. And this suggests how cultures of forced togetherness go beyond just wiping out the boundaries between work and the rest of one’s life, but also how the monoculture of Silicon Valley is perpetuated. If one is looking for “people we love to hang out with”, one is probably going to hire people that share a similar set of backgrounds, styles, and personalities. Hence, we find bands of mostly young men of white, Indian, and East Asian backgrounds who perpetuate college dorm life into their post-collegiate adulthood.

Of course, these are just simply two anecdotes, along with the concept writ large in Facebook’s Willow Village. I hope to dive deeper in these phenomena in future articles for the “Forced Togetherness Fridays” series, along with some positive stories of how things can go right instead of wrong with only a few cultural changes. And I welcome thoughts from others as I move forward, either sharing your own stories of forced togetherness in the workplace, or even counter-arguments in its favor. Until then, I plan to enjoy some quiet time working hard, by myself with just my cat for company.