We at CatSynth have long been interested in the intersection of art, technology and conceptual process. Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018 surveys over 50 years of video, computational and conceptual art, cleverly weaving them together into a single narrative whole. The three disciplines are united by the concept of a “program” or set of instructions through which the work of art unfolds, whether a computer program, instructions for a performance, or strict concept on a visual object. Video and lights abound, but there is also painting, dance, and more.

One of the artists who

At the opposite end of the video spectrum is his 1965 piece Magnet TV. A black-and-white CRT television set is disrupted by a large magnet, creating a unique but sometimes unpredictable pattern that is in its way rather spare and graceful.

In the first piece, the process is in the composition, arrangement, and looping of the various video clips. In the latter, it is the physics of the magnet and the CRT.

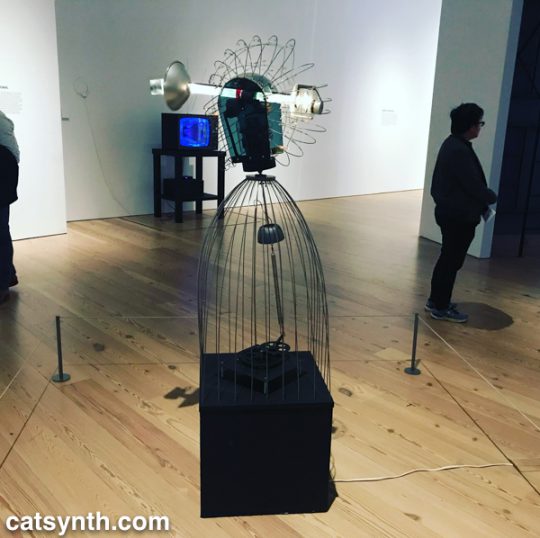

Motion and experiments with electronics are also at the heart of James L. Seawright’s contemporaneous piece, Searcher, which features gradual motion and changes in light. The shadows it casts are also part of the experience of the piece.

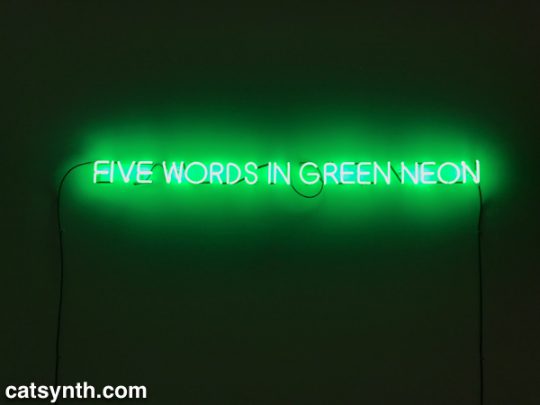

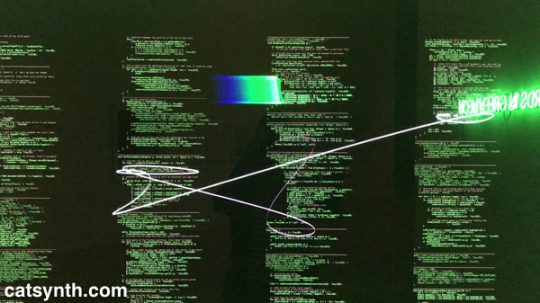

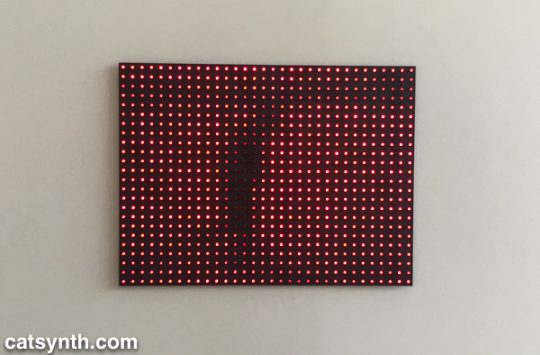

There is an interesting juxtaposition of one Joseph Kosuth’s classic neon text pieces, Five Words in Green Neon, and W. Bradford Paley’s Code Profiles, a Java program that generates images. They bring together the concepts of “text as art” and “code as art” – the message is the medium.

Paley’s code may be one of the most literal examples of the exhibition’s theme, but code need not be computer code as we think of it today. Many works from earlier periods were based on a series of instructions, where the instructions are the work and the performance or visual object are the expressions of said work. One such example is Sol Le Witt’s sculpture Five Towers. The three-dimension grids are assembled by a program with various combinations into a simple but beautiful result. I particularly enjoyed looking through it.

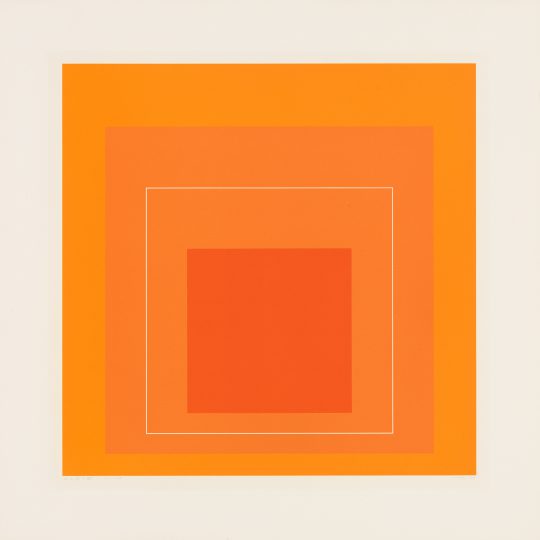

Josef Albers’ color-field rectangles can similarly be generated from a “program”. Like Le Witt’s piece, one could conceive of doing something like this with a computer, but neither artist chose to do so, instead being themselves the interpreters for the code.

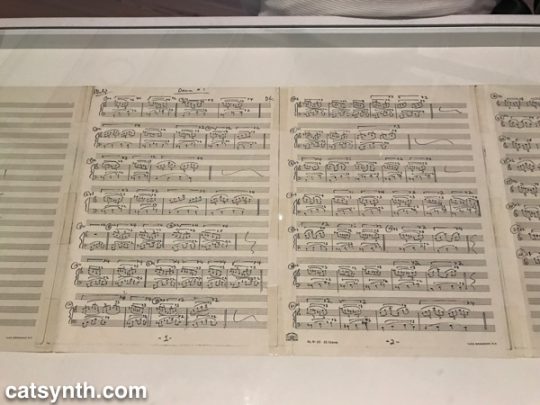

The performing arts have long been linked to programs, whether the traditional score or choreography, or more modern uses of algorithms or conceptual instructions.

Program, object, video and performance also come together Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Lorna. Lorna is an interactive video story on a laser disc (anyone else remember laser discs?). Users can determine how the story unfolds through one of three endings via a remote control. The screen and control are placed within a simulated apartment decked out entirely in leopard print, and the viewer is invited to sit in a comfy chair while the controlling the story. This self-guided performance is at once programmed, but also immersive in that the viewer becomes part of the piece, both in space and in terms of control.

Video permeates the entire exhibition, popping up directly and indirectly in at least half of the pieces, or not more. But

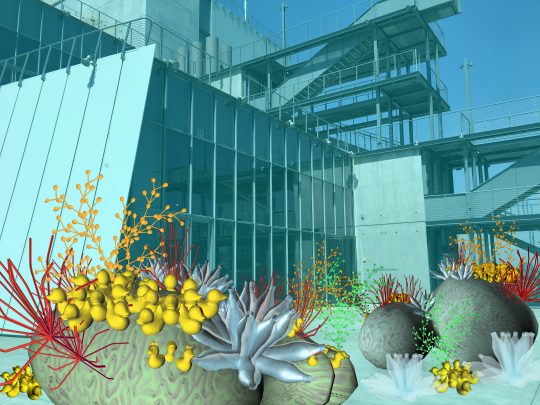

We conclude this survey with a new site-specific commission by Tamiko Thiel. She created an augmented-reality mobile app (in collaboration with developer /p) that overlays organic forms on the angular, geometric space of the museum’s outdoor terrace.

Thiel’s organic growths are beautiful and playful, but also have a darker aspect. Some resemble plastic refuse, and others coral formations. Both are emblematic of the crises facing our seas due to pollution and climate change. At the same time, the algorithmic process she uses, a formal grammar developed in 1968 by the Hungarian biologist and botanist Aristid Lindenmayer, is fascinating.

There were many more works in this exhibition that we can discuss in a single article. Each one had something compelling and different about it. For anyone interested in or curious about these forms of art, I highly recommend checking out this exhibit!

Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018 will be on display at the Whitney Museum of American Art through April 14, 2019.

Last week we lost Dennis M. Ritchie, whose work influenced much of what we do with computers today both as users and software developers.

Last week we lost Dennis M. Ritchie, whose work influenced much of what we do with computers today both as users and software developers.