On this dreary, rainy afternoon, we turn our attention southeast to the small town of Belen, New Mexico.

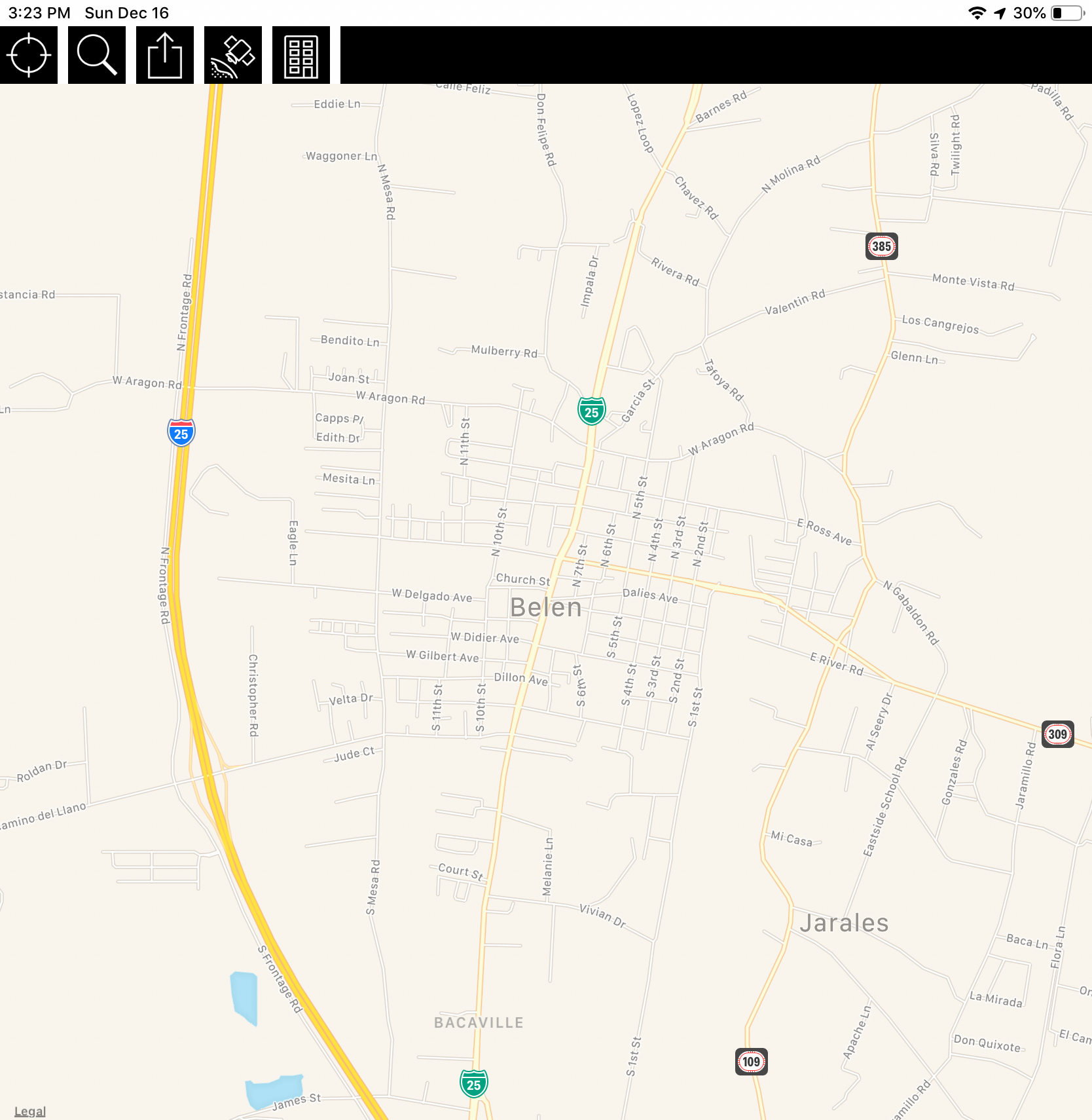

Belen is near the geographical center of New Mexico, south of Albuquerque. It is wedged between Interstate 25 to the west and the Rio Grande to the east. Business Loop 25 serves as the town’s Main Street, as well as the terminus for New Mexico state roads 314, 309, and 109. In its past, it served as a major railroad hub, even earning the nickname “Hub City.”

Belen is near the geographical center of New Mexico, south of Albuquerque. It is wedged between Interstate 25 to the west and the Rio Grande to the east. Business Loop 25 serves as the town’s Main Street, as well as the terminus for New Mexico state roads 314, 309, and 109. In its past, it served as a major railroad hub, even earning the nickname “Hub City.”

New Mexico is a place steeped in a unique character, bringing together Native American, Spanish, and Northern European heritage. Its landscape is bleak and beautiful. It has attracted generations of artists. Judy Chicago is one of those artists, and she chose to make her home in Belen.

Chicago is one of the founders of feminist art, a collection of art movements that serve to both create and critique art from the perspective of women. Early work by Chicago and others in this movement often turned assumptions upside down, sometimes slyly but sometimes not so subtly inserting womanhood into all types of artistic practice. But she has also been involved in work beyond feminism, notably The Holocaust Project.

Perhaps her best-known piece is The Dinner Party, which is now a permanent installation at the Brooklyn Museum in New York. I have had the opportunity to view it on multiple occasions.

The Dinner Party imagines women artists, thinkers, and leaders throughout history sitting at a large triangular table. Each of the place settings bears the name of an accomplished woman and the contents of her plate represent a stylized version of her accomplished. Additionally, the porcelain tiles surrounding the table identify nearly 1000 other women. The plates and their contents are often described as representing female sexuality through vulva-like, floral, and butterfly forms.

Returning from Brooklyn to Belen, we pick up the story in this weekend’s New York Times, about an effort by the town to host a museum dedicate to its famous resident and the art she creates and supports. This would seem to be a slam dunk for a town that appears to have fallen on hard times, but it apparently generated quite a bit of opposition.

The quarreling reflects not just the power of Ms. Chicago’s art to ignite emotions, but also the limits of tolerance in New Mexico, a state long known as a welcoming mecca for artists. Evangelical Christian leaders in Belen have mobilized to thwart the project, calling Ms. Chicago’s art pornographic and indecent.

[link]

“I love fine art, but I would never want to see a vagina hanging on my wall,” said John K. Thompson, 62, a retired stockbroker.

It seems odd that the state that celebrates Georgia O’Keefe would have a problem with vaginal imagery in art. So why this place, and why now?

Paula Castillo [a sculptor who was born and raised in Belen] believes that the friction reflects the town’s own evolving dynamics…Belen has long been home to Hispanic families whose roots in New Mexico go back centuries. Religious affiliations are in flux, but many remain members of the Roman Catholic Church, which has not voiced opposition to the museum.

But after meeting with pastors from the evangelical churches opposing the museum, Ms. Castillo said she concluded that much of the resistance appeared to come from relative newcomers who brought more conservative sensibilities with them.

“There’s a level of nuance to what’s going on that’s been neglected,” Ms. Castillo said. “Belen and the rest of New Mexico can be very welcoming, but it’s easy to forget the influence that some churches now have.”

Indeed, I had come to think that despite the power of conservative Christians in our politics, the somewhat cartoonish cries of “indecency” in art were a sad joke from my past. Not surprising, this has been an upsetting experience for Chicago herself. I can only imagine what it feels like to feel welcomed in a community, only to have part of that community turn against you…

Responding to the critics, Ms. Chicago and Mr. Woodman in November withdrew their offer to work with Belen’s municipal government on the proposed museum. “The whole experience has been very painful,” said Ms. Chicago, explaining how she followed the debate over the museum and her work on social media while she was traveling in Brazil

It seems like a potential opportunity missed, especially as one sees how embracing minimalist Donald Judd put Marfa, Texas, on the map and has made it a cultural destination. Indeed, Marfa is on my bucket list, especially after seeing it featured in one of the last episodes of Anthony Bourdain’s show. Whether Belen gives up its chance to be another Marfa remains to be seen.

See more of New Mexico and many other fascinating places in our Highway☆ app, available on the Apple App Store and Google Play Store.

We initially entered from the northeast on I-76. The road was relatively straight here amidst softly rolling hills of the High Plains. The landscape is dotted with farms amidst open grassland. The Rocky Mountains appear to rise from the plains quite suddenly, as does the city of Denver.

We initially entered from the northeast on I-76. The road was relatively straight here amidst softly rolling hills of the High Plains. The landscape is dotted with farms amidst open grassland. The Rocky Mountains appear to rise from the plains quite suddenly, as does the city of Denver.

On that original family trip, we did not actually stop in Denver, but here we will do so. We turn south on I-25 along the edge of downtown Denver, passing through the interchange with I-70 known as “The Mousetrap.” We exit with US 6 which is surprisingly enough Sixth Avenue in Denver. Actually, it’s a freeway, the “Sixth Avenue Freeway.” Heading east in the freeway, it empties out onto city streets near the Santa Fe Arts District. A quick look at the websites for the galleries along the corridor suggests a relatively conservative selection, though I did see some interesting things from Sparks. Further north we find the

On that original family trip, we did not actually stop in Denver, but here we will do so. We turn south on I-25 along the edge of downtown Denver, passing through the interchange with I-70 known as “The Mousetrap.” We exit with US 6 which is surprisingly enough Sixth Avenue in Denver. Actually, it’s a freeway, the “Sixth Avenue Freeway.” Heading east in the freeway, it empties out onto city streets near the Santa Fe Arts District. A quick look at the websites for the galleries along the corridor suggests a relatively conservative selection, though I did see some interesting things from Sparks. Further north we find the

We leave Denver on I-70 and head into the mountains, on one of the most spectacular stretches of interstate highway in the country. At the Continental Divide, there are two options. One can stay on I-70 through the Eisenhower Tunnel, or take a detour on US 6 up through Loveland Pass. We opted for the latter on that original trip, with spectacular views of mountains in all directions, and a chance to walk on a patch of hardened snow and ice…in August. Not surprisingly, it was quite cold. I don’t have any pictures from that trip, but here is what the pass looks like today:

We leave Denver on I-70 and head into the mountains, on one of the most spectacular stretches of interstate highway in the country. At the Continental Divide, there are two options. One can stay on I-70 through the Eisenhower Tunnel, or take a detour on US 6 up through Loveland Pass. We opted for the latter on that original trip, with spectacular views of mountains in all directions, and a chance to walk on a patch of hardened snow and ice…in August. Not surprisingly, it was quite cold. I don’t have any pictures from that trip, but here is what the pass looks like today:

I-70 and US 6 descend from the Rocky Mountains into the town of Grand Junction, where they meet US 50. One can exit the interstate here and travel on State Highway 340 through Grand Junction and Fruita to Colorado National Monument.

I-70 and US 6 descend from the Rocky Mountains into the town of Grand Junction, where they meet US 50. One can exit the interstate here and travel on State Highway 340 through Grand Junction and Fruita to Colorado National Monument.

From there, we took I-70/US 6/US 50 west into Utah. But, we later reentered Colorado from the Four Corners along US 160. The quiet and stark southwestern landscape particularly appealed to me then and still does now. We then headed north on what was then US 666 (the “Devil’s Highway”), but has since been renumbered as US 491. Honestly, I wish they kept the 666 designation. But it is what it is. The two highways separate in the town of Cortez, and one can continue on 160 east to Mesa Verde National Park.

From there, we took I-70/US 6/US 50 west into Utah. But, we later reentered Colorado from the Four Corners along US 160. The quiet and stark southwestern landscape particularly appealed to me then and still does now. We then headed north on what was then US 666 (the “Devil’s Highway”), but has since been renumbered as US 491. Honestly, I wish they kept the 666 designation. But it is what it is. The two highways separate in the town of Cortez, and one can continue on 160 east to Mesa Verde National Park.