Multiple friends and readers have noted the similarities in my observations and critiques of “forced togetherness” in the tech industry to the eponymous tech giant in The Circle, Dave Eggers’ 2013 novel. So in today’s edition of the series, we examine The Circle more closely, and what we can learn from its example. We are going to focus specifically on the Eggers novel and not the film adaptation starring Emma Watson and Tom Hanks – and there will be some spoilers, though we won’t give away the ending.

The Circle chronicles a critical stage of the evolution of the company of the same name, as seen through the eyes of a young newcomer, Mae Holland. The book can largely be divided into the overlapping stories of Mae’s experience working inside the company, and the larger implications of The Circle’s ambitions and vision on society as a whole. The two are intertwined, as The Circle intends to remake society into a utopia based on its own internal culture. But that internal culture, especially in the novel’s first act, is what most concerns us here.>

We first encounter Mae, a recent college grad, as she is leaving behind her dead-end job in her tiny hometown in the Central Valley. The town, Longfield, is described as being halfway between Fresno and Tranquility, suggesting that it might be modeled after the real town of Kerman, California. But I digress. Mae scores an opportunity to work at The Circle via her friend and former college roommate Annie, who is a senior member of The Circle’s leadership focusing on regulatory issues.

The company’s campus has details that could easily have been drawn from the real-life headquarters of Google or Facebook. Similarly, the company’s culture seems like Google or Facebook on steroids. There are food and recreational opportunities everywhere, including regular parties and over-the-top live entertainment from well-known bands. Indeed the fitness, medical facilities, and cafeterias seem mundane compared to the over-the-top cultural aspects that scream “forced togetherness.” It is clear from the start that the goal is to keep Circlers on campus as much as possible, whether or not they are working or playing. Perhaps this hit a little closer-to-home for me than other readers, as I see this as the most cynical and insidious aspect of tech-company culture.

We see the culture of The Circle seeping into Mae’s actual job, which is as a customer-experience agent. The job itself is straightforward and reasonable, she answers questions from clients (think folks like us who sometimes buy Facebook ads, incorporate Paypal payments, etc.). Clients can rate her service, and that is factored into her job performance, with the goal to get as close to a 100% rating as possible. She also gets pinned to clients she has previously helped, allowing her to develop relationships with them. There is a steady queue of incoming requests. Stressful and high-pressured, perhaps, but nothing out of the ordinary for work. Things get darker as Mae discovers that her social participation in life at The Circle is judged as significantly, of not more than, her job performance. After neglecting to set up her social profiles (similar to a Facebook profile but with internal-and-external facing personae), she is chastised by the annoyingly perky social-media representatives who come to make sure she follows through and sets it up. She is scolded for not being on campus over a weekend. Mind you, not that she wasn’t working, but that she wasn’t present. When she explains that she was visiting her parents and her father’s multiple sclerosis, the topic turns to why she hasn’t joined any Circle online groups for children of people with MS. Even her solitary joy of kayaking is questioned by one of the representatives, who not only pressures her to join kayaking-enthusiast groups but even suggests they should do so together as this is a passion of his as well. Later on, Mae is called into her boss’ office who says she is doing a great job but then gives her a serious dressing down about the fact that she is falling behind on social media participation – people at the Circle are ranked by a social-media participation score. Again, she is scolded for being off campus, visiting her family, and missing yet another “awesome” party.

While reading all the social pressure and lack of personal autonomy being thrown at Mae, I felt my own heart race and my own anxiety levels rise. Here was everything I rail against in this series, taken to its utmost extreme. Don’t get me wrong, the campus is amazing and beautiful and full of opportunities – and the fact that Mae’s father finally has access to state-of-the-art care for his MS is great. But these benefits come at the cost of a lack of boundaries and personal autonomy, things we learn are anathema to The Circle’s vision and business model as well as company culture.

Things come to a head in both the business and personal aspects. The Circle has developed tiny low-cost and low-powered HD camera that can be placed anywhere or on anyone. They launch an initiative to have elected leaders “go transparent”, i.e., wear a live-streaming video camera at all times. Meanwhile, Mae’s job is going well as she determines to rise to the top in the company’s social-media rankings, but her life back home is falling apart. The cameras and such are quite intrusive for her parents, and her ex-boyfriend (and professional Luddite) Mercer breaks off his contact with her after her attempt to promote his deer-antler-chandelier business backfires spectacularly. This leads her to seek solace in her one solitary joy, kayaking. It’s late and she steals a kayak from her friends who run a small rental business. It is foggy that night, but she paddles out far into the bay and ends up near the real-life Red Rock Island and Richmond-San-Rafael Bridge. I could see myself seeking out a similar solitary passion in such a stressful situation, such as a “fun with highways” trip. Unbeknownst to her, there was one of The Circle’s tiny cameras near the kayak shop, and her entire caper is recorded and seen by the company’s leaders. Not only does this get her in trouble for potentially committing a crime, it also leads to another round of recriminations about her autonomy and distance from the rest of the company.

As Act 1 of the novel comes to a close, Mae makes a fateful decision to salvage her career by going “transparent.” Act 2 follows the transparent Mae has she live-streams life on the campus and gets intertwined with things darker and darker about The Circle’s dystopian ambitions, which include a devotion to transparency and demonization of privacy. Forced-togetherness becomes not just part of the company culture, but the vision for society as a whole! Everyone connected at all times, full transparency, no boundaries, no privacy. This ghastly possibility is what The Circle promotes as a utopia.

When Mae was suffering under the cultural pressure of The Circle in Act 1, she remained a sympathetic character. But as she embraces The Circle’s internal and external vision, she becomes a much less sympathetic character, and I began to distrust and even detest her. But at the same time, her ex Mercer, who is set up as the skeptical foil to The Circle’s vision, is not particularly likable, either. He is a self-righteous prig. Indeed, in the end, there is not one character who comes out positive. Dislikable and untrustworthy characters are a mainstay of Eggers’ fiction and make for great reading. But in this cas,e they hit close enough to home to be rather disconcerting.

It is, of course, important to remember that The Circle is fiction. None of the campuses I have visited, none of the businesses I have seen in depth, are nearly as sinister, though each has aspects that could lead to The Circle, both inside and out. I hope we can figure out how to balance these competing challenges and they become closer to reality without going completely to the extreme in the other direction. We don’t want to become Mae, but we shouldn’t have to become Mercer to avoid becoming her. The technology is amazing, as long as we retain control and autonomy around it. And we see this playing out in real life right now (e.g., consider the recent privacy scandals involving Facebook) and with increasing public awareness. So there is hope.

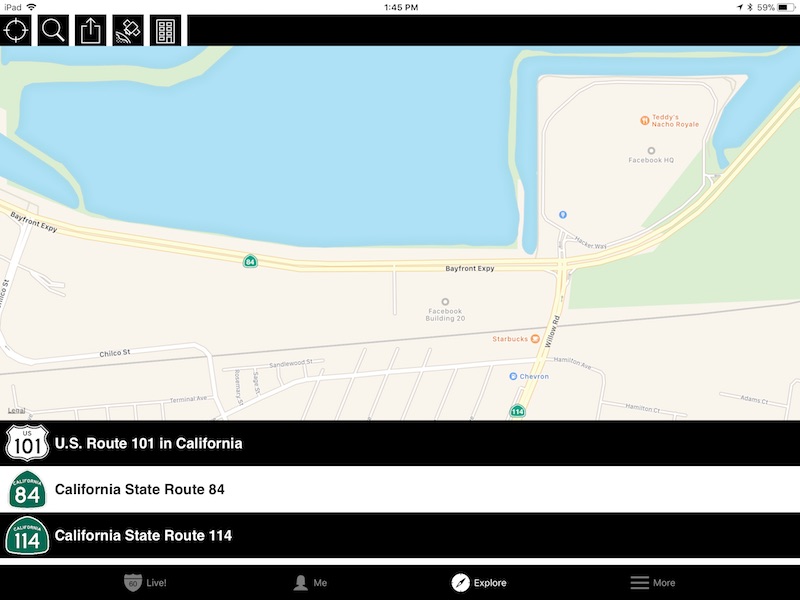

As seen in the above screenshot from our

As seen in the above screenshot from our