Multiple friends and readers have noted the similarities in my observations and critiques of “forced togetherness” in the tech industry to the eponymous tech giant in The Circle, Dave Eggers’ 2013 novel. So in today’s edition of the series, we examine The Circle more closely, and what we can learn from its example. We are going to focus specifically on the Eggers novel and not the film adaptation starring Emma Watson and Tom Hanks – and there will be some spoilers, though we won’t give away the ending.

The Circle chronicles a critical stage of the evolution of the company of the same name, as seen through the eyes of a young newcomer, Mae Holland. The book can largely be divided into the overlapping stories of Mae’s experience working inside the company, and the larger implications of The Circle’s ambitions and vision on society as a whole. The two are intertwined, as The Circle intends to remake society into a utopia based on its own internal culture. But that internal culture, especially in the novel’s first act, is what most concerns us here.>

We first encounter Mae, a recent college grad, as she is leaving behind her dead-end job in her tiny hometown in the Central Valley. The town, Longfield, is described as being halfway between Fresno and Tranquility, suggesting that it might be modeled after the real town of Kerman, California. But I digress. Mae scores an opportunity to work at The Circle via her friend and former college roommate Annie, who is a senior member of The Circle’s leadership focusing on regulatory issues.

The company’s campus has details that could easily have been drawn from the real-life headquarters of Google or Facebook. Similarly, the company’s culture seems like Google or Facebook on steroids. There are food and recreational opportunities everywhere, including regular parties and over-the-top live entertainment from well-known bands. Indeed the fitness, medical facilities, and cafeterias seem mundane compared to the over-the-top cultural aspects that scream “forced togetherness.” It is clear from the start that the goal is to keep Circlers on campus as much as possible, whether or not they are working or playing. Perhaps this hit a little closer-to-home for me than other readers, as I see this as the most cynical and insidious aspect of tech-company culture.

We see the culture of The Circle seeping into Mae’s actual job, which is as a customer-experience agent. The job itself is straightforward and reasonable, she answers questions from clients (think folks like us who sometimes buy Facebook ads, incorporate Paypal payments, etc.). Clients can rate her service, and that is factored into her job performance, with the goal to get as close to a 100% rating as possible. She also gets pinned to clients she has previously helped, allowing her to develop relationships with them. There is a steady queue of incoming requests. Stressful and high-pressured, perhaps, but nothing out of the ordinary for work. Things get darker as Mae discovers that her social participation in life at The Circle is judged as significantly, of not more than, her job performance. After neglecting to set up her social profiles (similar to a Facebook profile but with internal-and-external facing personae), she is chastised by the annoyingly perky social-media representatives who come to make sure she follows through and sets it up. She is scolded for not being on campus over a weekend. Mind you, not that she wasn’t working, but that she wasn’t present. When she explains that she was visiting her parents and her father’s multiple sclerosis, the topic turns to why she hasn’t joined any Circle online groups for children of people with MS. Even her solitary joy of kayaking is questioned by one of the representatives, who not only pressures her to join kayaking-enthusiast groups but even suggests they should do so together as this is a passion of his as well. Later on, Mae is called into her boss’ office who says she is doing a great job but then gives her a serious dressing down about the fact that she is falling behind on social media participation – people at the Circle are ranked by a social-media participation score. Again, she is scolded for being off campus, visiting her family, and missing yet another “awesome” party.

While reading all the social pressure and lack of personal autonomy being thrown at Mae, I felt my own heart race and my own anxiety levels rise. Here was everything I rail against in this series, taken to its utmost extreme. Don’t get me wrong, the campus is amazing and beautiful and full of opportunities – and the fact that Mae’s father finally has access to state-of-the-art care for his MS is great. But these benefits come at the cost of a lack of boundaries and personal autonomy, things we learn are anathema to The Circle’s vision and business model as well as company culture.

Things come to a head in both the business and personal aspects. The Circle has developed tiny low-cost and low-powered HD camera that can be placed anywhere or on anyone. They launch an initiative to have elected leaders “go transparent”, i.e., wear a live-streaming video camera at all times. Meanwhile, Mae’s job is going well as she determines to rise to the top in the company’s social-media rankings, but her life back home is falling apart. The cameras and such are quite intrusive for her parents, and her ex-boyfriend (and professional Luddite) Mercer breaks off his contact with her after her attempt to promote his deer-antler-chandelier business backfires spectacularly. This leads her to seek solace in her one solitary joy, kayaking. It’s late and she steals a kayak from her friends who run a small rental business. It is foggy that night, but she paddles out far into the bay and ends up near the real-life Red Rock Island and Richmond-San-Rafael Bridge. I could see myself seeking out a similar solitary passion in such a stressful situation, such as a “fun with highways” trip. Unbeknownst to her, there was one of The Circle’s tiny cameras near the kayak shop, and her entire caper is recorded and seen by the company’s leaders. Not only does this get her in trouble for potentially committing a crime, it also leads to another round of recriminations about her autonomy and distance from the rest of the company.

As Act 1 of the novel comes to a close, Mae makes a fateful decision to salvage her career by going “transparent.” Act 2 follows the transparent Mae has she live-streams life on the campus and gets intertwined with things darker and darker about The Circle’s dystopian ambitions, which include a devotion to transparency and demonization of privacy. Forced-togetherness becomes not just part of the company culture, but the vision for society as a whole! Everyone connected at all times, full transparency, no boundaries, no privacy. This ghastly possibility is what The Circle promotes as a utopia.

When Mae was suffering under the cultural pressure of The Circle in Act 1, she remained a sympathetic character. But as she embraces The Circle’s internal and external vision, she becomes a much less sympathetic character, and I began to distrust and even detest her. But at the same time, her ex Mercer, who is set up as the skeptical foil to The Circle’s vision, is not particularly likable, either. He is a self-righteous prig. Indeed, in the end, there is not one character who comes out positive. Dislikable and untrustworthy characters are a mainstay of Eggers’ fiction and make for great reading. But in this cas,e they hit close enough to home to be rather disconcerting.

It is, of course, important to remember that The Circle is fiction. None of the campuses I have visited, none of the businesses I have seen in depth, are nearly as sinister, though each has aspects that could lead to The Circle, both inside and out. I hope we can figure out how to balance these competing challenges and they become closer to reality without going completely to the extreme in the other direction. We don’t want to become Mae, but we shouldn’t have to become Mercer to avoid becoming her. The technology is amazing, as long as we retain control and autonomy around it. And we see this playing out in real life right now (e.g., consider the recent privacy scandals involving Facebook) and with increasing public awareness. So there is hope.

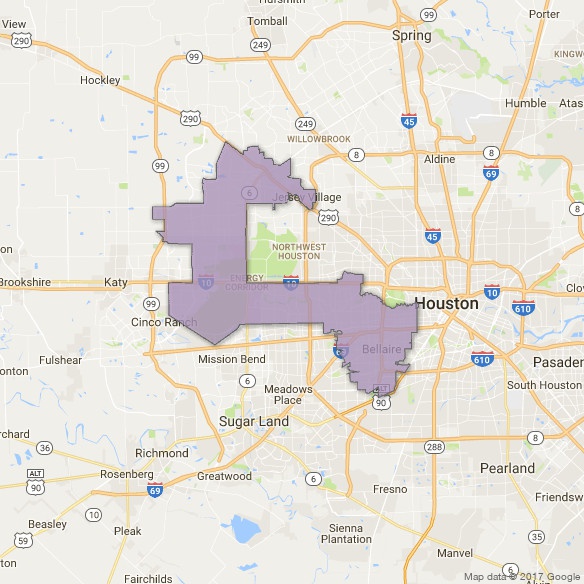

The southeast “bulge” part of the district includes sections of Houston that lie within the I-610 loop, or “Inner Loop”. I-610 separates the downtown sections of Houston from outer neighborhoods and surrounding communities, including towns like Southside Place. It is bisected west-to-east by the new I-69 (US 59). The area where these two highways intersect would not look out of place in Los Angeles.

The southeast “bulge” part of the district includes sections of Houston that lie within the I-610 loop, or “Inner Loop”. I-610 separates the downtown sections of Houston from outer neighborhoods and surrounding communities, including towns like Southside Place. It is bisected west-to-east by the new I-69 (US 59). The area where these two highways intersect would not look out of place in Los Angeles.

Heading north and west, we come to the middle section of the district, which is largely a horizontal rectangle bounded by the mighty I-10 to the north, and which extends almost to Katy in the west. Beltway 8, also known as the Sam Houston Parkway/Tollway, bisects this segment of the district. Just to the west of the beltway are the Briarforest neighborhood and the ominously named Energy Corridor. Not surprisingly, several major energy corporations have operations in this area, as do several other businesses. The Buffalo Bayou – we at CatSynth are still not entirely sure what separates a bayou from a river – cuts through the district. It was subject to major flooding during Hurricane Harvey. In addition to the bayou itself cresting at record levels above flood stage. releases from the Barker Reservoir caused severe flooding in adjacent low-lying neighborhoods. We have sources that have informed us that the floodwaters in the Energy Corridor area were most unpleasant.

Heading north and west, we come to the middle section of the district, which is largely a horizontal rectangle bounded by the mighty I-10 to the north, and which extends almost to Katy in the west. Beltway 8, also known as the Sam Houston Parkway/Tollway, bisects this segment of the district. Just to the west of the beltway are the Briarforest neighborhood and the ominously named Energy Corridor. Not surprisingly, several major energy corporations have operations in this area, as do several other businesses. The Buffalo Bayou – we at CatSynth are still not entirely sure what separates a bayou from a river – cuts through the district. It was subject to major flooding during Hurricane Harvey. In addition to the bayou itself cresting at record levels above flood stage. releases from the Barker Reservoir caused severe flooding in adjacent low-lying neighborhoods. We have sources that have informed us that the floodwaters in the Energy Corridor area were most unpleasant.

The final section of the district cuts an inverted “L” between State Highway 6 and State Highway 99, the outermost loop around Houston, bounded on top by US 290. In all, the district has an odd shape indeed, but not so odd when one considers the tradition of gerrymandering, an art which has been taken to new heights by Texas’ Republican-controlled state government. Its shape has long preserved it as a safe Republican district – it has elected Republicans to Congress consistently since George H.W. Bush in 1966. But the city and surrounding area have been changing, and it is seen as vulnerable to flip to 2018.

The final section of the district cuts an inverted “L” between State Highway 6 and State Highway 99, the outermost loop around Houston, bounded on top by US 290. In all, the district has an odd shape indeed, but not so odd when one considers the tradition of gerrymandering, an art which has been taken to new heights by Texas’ Republican-controlled state government. Its shape has long preserved it as a safe Republican district – it has elected Republicans to Congress consistently since George H.W. Bush in 1966. But the city and surrounding area have been changing, and it is seen as vulnerable to flip to 2018.

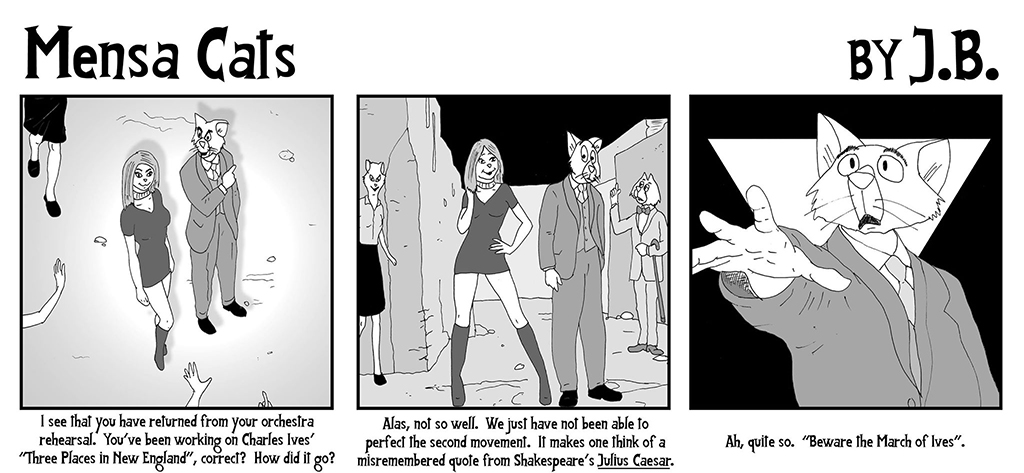

We begin with B Kilban. An artist originally from Connecticut, he got his start as a cartoonist here in San Francisco, drawing for Playboy. It was at Playboy where his distinctive cat cartoons were discovered by editor Michelle Urry. This led to his most well-known book, Cat. You have probably seen his cats both in formal cartoons and adorning many products. Kilban passed away in 1990, but his legacy lives on through his books and syndication of his images. You can find out more at his official website

We begin with B Kilban. An artist originally from Connecticut, he got his start as a cartoonist here in San Francisco, drawing for Playboy. It was at Playboy where his distinctive cat cartoons were discovered by editor Michelle Urry. This led to his most well-known book, Cat. You have probably seen his cats both in formal cartoons and adorning many products. Kilban passed away in 1990, but his legacy lives on through his books and syndication of his images. You can find out more at his official website  Of course, an article on cat cartoonists must include Jim Davis, the creator of Garfield. Davis grew up on a farm in Indiana with his parents, brother, and 25 cats. While the main human character in Davis’ cartoons, Jon Arbuckle is also a cartoonist who grew up on a farm, the spoiled and overweight Garfield seems nothing like a farm cat. Indeed, his disdain for the concept of catching mice is a frequent topic of the strips. Many an orange male cat has been named “Garfield” in the character’s honor.

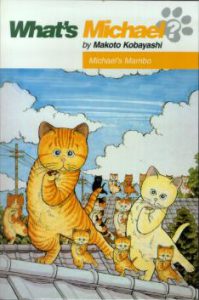

Of course, an article on cat cartoonists must include Jim Davis, the creator of Garfield. Davis grew up on a farm in Indiana with his parents, brother, and 25 cats. While the main human character in Davis’ cartoons, Jon Arbuckle is also a cartoonist who grew up on a farm, the spoiled and overweight Garfield seems nothing like a farm cat. Indeed, his disdain for the concept of catching mice is a frequent topic of the strips. Many an orange male cat has been named “Garfield” in the character’s honor. One of the best-known works of Japanese manga artist Makoto Kobayashi also features an orange cat. What’s Michael? chronicles the adventures of a shorthair tabby named Michael and his many feline friends. It was originally released in serial form in Japan’s Weekly Morning manga magazine, but it now available in the U.S. as well via Dark Horse Comics. The stories are a mix of the mundane and surreal, with Michael sometimes appearing differently than the orange shorthair title cat, and sometimes even dying in certain episodes.

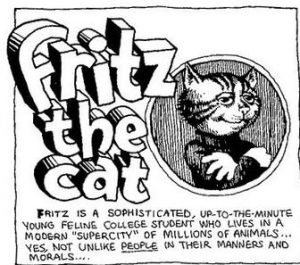

One of the best-known works of Japanese manga artist Makoto Kobayashi also features an orange cat. What’s Michael? chronicles the adventures of a shorthair tabby named Michael and his many feline friends. It was originally released in serial form in Japan’s Weekly Morning manga magazine, but it now available in the U.S. as well via Dark Horse Comics. The stories are a mix of the mundane and surreal, with Michael sometimes appearing differently than the orange shorthair title cat, and sometimes even dying in certain episodes. And then there is Fritz the Cat, created by the legendary R. Crumb. Fritz originally appeared in Crumb’s homemade comic book “Cat Life”. Originally based on the family cat, Fritz became anthropomorphic in later iterations, evolving into the hedonistic con-artist character that was a mainstay of underground comix in the 1960s. Fritz’s adventures in a New York-like mega-city populated entirely by anthropomorphic animals often devolved into chaos with unusual sexual escapades. In the 1970s, Fritz the Cat was made into an animated feature film by Ralph Bakshi.

And then there is Fritz the Cat, created by the legendary R. Crumb. Fritz originally appeared in Crumb’s homemade comic book “Cat Life”. Originally based on the family cat, Fritz became anthropomorphic in later iterations, evolving into the hedonistic con-artist character that was a mainstay of underground comix in the 1960s. Fritz’s adventures in a New York-like mega-city populated entirely by anthropomorphic animals often devolved into chaos with unusual sexual escapades. In the 1970s, Fritz the Cat was made into an animated feature film by Ralph Bakshi. Another underground comix artist Gilbert Shelton created a well-known feline character. Known simply as “Fat Freddy’s Cat”, he initially appeared in Shelton’s Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers strip about a trio of stoner characters in the 1960s before getting his own strip. A standalone series, The Adventures of Fat Freddy’s Cat was published in the 1970s and expanded in a 1980s release.

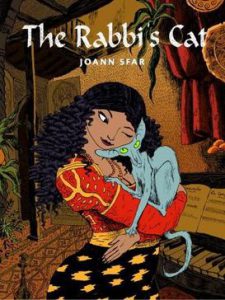

Another underground comix artist Gilbert Shelton created a well-known feline character. Known simply as “Fat Freddy’s Cat”, he initially appeared in Shelton’s Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers strip about a trio of stoner characters in the 1960s before getting his own strip. A standalone series, The Adventures of Fat Freddy’s Cat was published in the 1970s and expanded in a 1980s release. Joann Sfar is a French comics artist. Influenced by the European comics artists of the 20th century including the great Moebius (Jean Giraud), he has a distinctive style that is at once more realistic and fanciful. One of his most well-known series is The Rabbi’s Cat, first released as a comic book in 2005 and later adapted into a film in 2011, which he directed. The main feline character is a cat who has the ability to speak and lives with a rabbi and his daughter in the Jewish community of 1920s Algeria. Sfar’s Jewish heritage runs through many of his works, but no more directly than in The Rabbi’s Cat. In addition to the books, we at CatSynth recommend seeing the film (which is gorgeous) in the original French.

Joann Sfar is a French comics artist. Influenced by the European comics artists of the 20th century including the great Moebius (Jean Giraud), he has a distinctive style that is at once more realistic and fanciful. One of his most well-known series is The Rabbi’s Cat, first released as a comic book in 2005 and later adapted into a film in 2011, which he directed. The main feline character is a cat who has the ability to speak and lives with a rabbi and his daughter in the Jewish community of 1920s Algeria. Sfar’s Jewish heritage runs through many of his works, but no more directly than in The Rabbi’s Cat. In addition to the books, we at CatSynth recommend seeing the film (which is gorgeous) in the original French. Another classic of feline cartoons is Krazy Kat, by George Herriman. It had a long run as a comic strip in American newspapers from 1913 to 1944 when Herriman died. The strip was based around the ostensibly simple cat-and-mouse trip, with the cat named Krazy being taunted and tormented by a mouse Ignatz who is often shown throwing bricks at Krazy’s head. Krazy speaks in a very stylized mixture of English and other languages and is of indeterminate gender – though inexplicably smitten with Ignatz.

Another classic of feline cartoons is Krazy Kat, by George Herriman. It had a long run as a comic strip in American newspapers from 1913 to 1944 when Herriman died. The strip was based around the ostensibly simple cat-and-mouse trip, with the cat named Krazy being taunted and tormented by a mouse Ignatz who is often shown throwing bricks at Krazy’s head. Krazy speaks in a very stylized mixture of English and other languages and is of indeterminate gender – though inexplicably smitten with Ignatz.