Most visits to New York include a stop at the temple of modernism, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). But this was my first visit since the massive multi-year expansion and renovation was completed. In some ways, it seems that not much has changed, but in other ways it has changed considerably, starting the members-only entranceway leading to a larger and more open lobby.

The second=floor atrium remains very much the same as it has been since the expansion in the early 2000s, a cavernous space looking up to all exhibition floors of the museum. It often is used to display monumental pieces or immersive performance works. Handles, a performance and sculptural piece by Haegue Yang combined both.

The name refers to the handles on all of the sculptural elements that allowed them to be slowly moved around the space by the performers. In between these motions, the performers gathered for vocal chanting that brought to mind the work of Pauline Oliveros. The sculptures and wall and floor elements had a simple geometric quality that reminded me of children’s building blocks. They also had bells and other sound elements mounted, again something that brought to mind Oliveros.

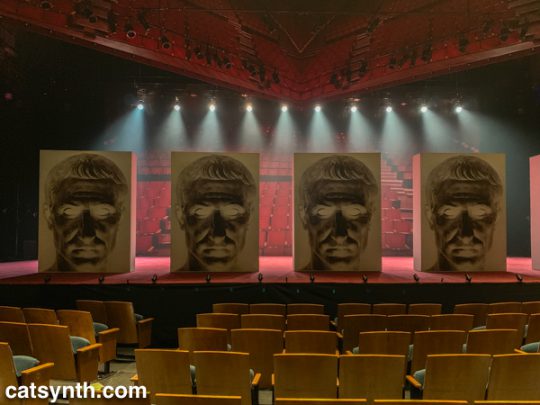

From the atrium, I always head immediately to the sixth floor and gradually work my way back down. The top floor featured Surrounds, an exhibition of large-scale installations by a diverse collection of contemporary artists. Some, like Mark Manders‘ Room with Chairs and Factory, were large singular pieces, with a gallery-sized replica of a factory. Others were large compositions of smaller elements. For example, Dayanita Singh‘s Museum of Chance was composed of numerous photograph prints made by the artist, assembled into large modular panels that could be easily rearranged in any number of configurations.

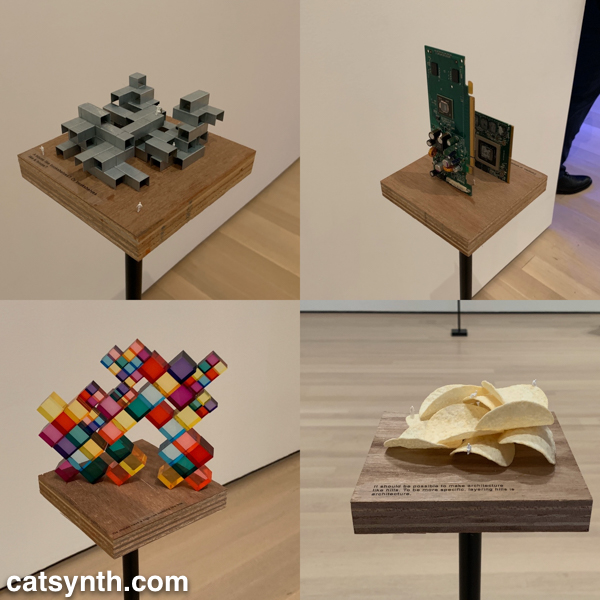

In his installation Architecture Is Everywhere, Sou Fujimoto challenges us to see the “architecture” in everyday objects. His installation is a field of small objects ranging from colored geometric design elements to potato chips placed on an array of pedestals.

The “architecture” in each object is readily apparent when one is invited to see it. Even the potato chips are curvilinear forms that might be at home in a 1960s futurist public space.

Perhaps the most of fun of all the installations was Sarah Sze’s Triple Point (Pendulum). A colorful collection of everyday objects are arranged, somewhat precariously, around a circle as a pendulum swings freely above, threatening mayhem of destruction. However, that never happens and instead, we end up with an intricate but chaotic dance.

The name of the piece, which derives from the “triple point” where water can exist simultaneously as ice, liquid, and vapor, illustrates the sense mix of chaotic and coexistence in the installation.

Descending to the fifth floor, some of the changes to the museum became more apparent. The terrace cafe overlooking the sculpture garden had been removed (actually, moved to a new location on the sixth floor), and replaced by an open gallery space showing various sculptures by Constantin Brancusi.

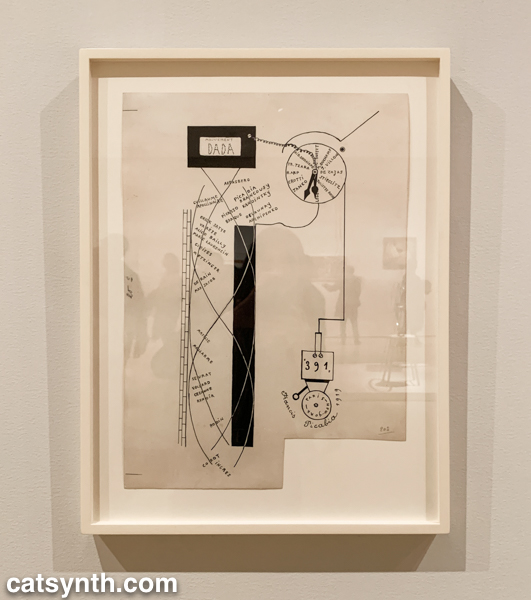

The remainder of the fifth floor and the entirety of the fourth floor housed an expanded and increasingly labyrinthine set of galleries for the permanent collection. The first gallery, which featured the oldest and most traditional works such as Van Gogh and Matisse, was by far the most crowded space in the entire museum. I quickly left to find some more open spaces and truly modern works, which began to appear in the 1910s and 1920s. In addition to Dada favorites, there were works celebrating machines, industry and the break with traditional forms of painting. Francis Picabia’s Dada Movement and Man Ray’s chess set are exemplars of these directions.

Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes‘ Silence depicts a musical instrument attached to machinery, perhaps speaking to the contradictory nature of music made by machines.

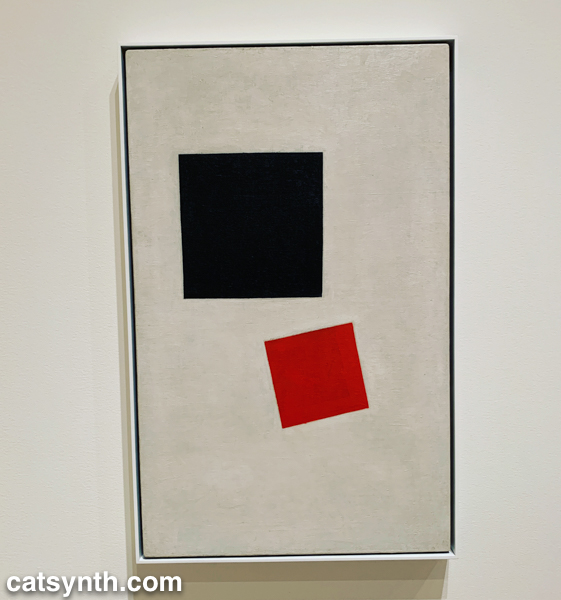

There was also a lively world of modernism and abstraction in Russia before the 1917 revolution, as exemplified by Kazimir Malevich’s minimalist Supremacist Composition: Airplane Flying.

The expanded galleries included a room of design pieces from the interwar period (these were previously displayed in the separate design gallery on a rotating basis).

There was also a new space devoted to so-called “outsider artists” of the period, including Morris Hirshfield. I was particularly drawn to his portrait of a white cat titled Angora Cat.

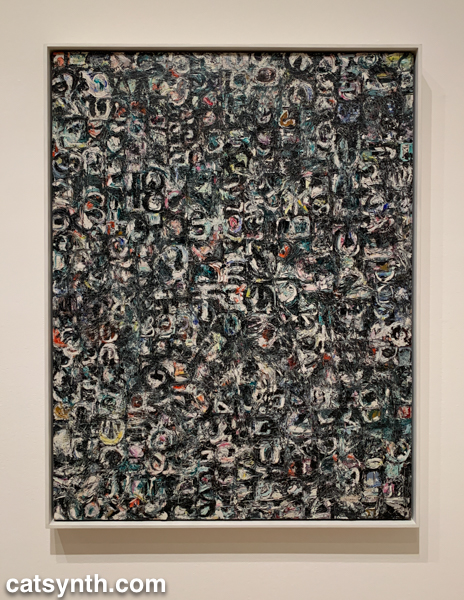

The collection continued on the fourth floor with the period between the end of World War II and the 1970s. This is usually my favorite section to linger in, with many iconic works of the 20th century. The Jackson Pollock’s are of course back on full display, but so is Lee Krasner, who is finally getting her due as a leading abstract expressionist painter.

The expanded galleries have given more room for women and other underrepresented artists. The photography of Helen Levitt was featured in a room that also included artists depicting life in Harlem in the 1950s. I particularly liked this photograph of hers with a black cat.

This sculpture by Barbara Hepworth is quite minimal, with the perfection of the sphere balancing with the “squishier” curves of the taller element.

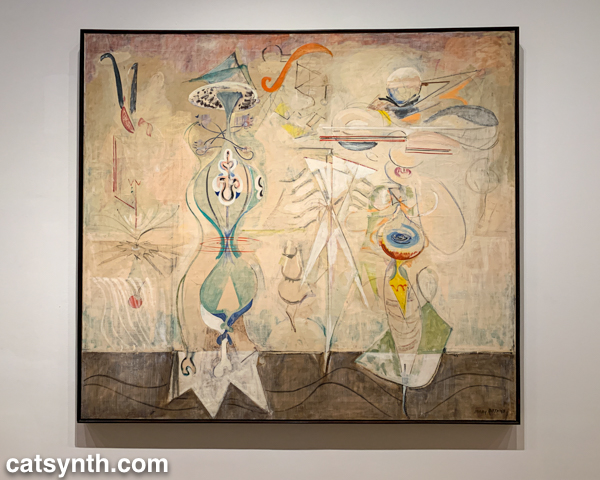

There were also pieces that showed the works of artists beyond their most well-known. I would not have guessed this painting with other-worldly plant-like creatures as the work of Mark Rothko were it not for the title card.

There were of course pieces that did exemplify artists as we know them. Ellsworth Kelly had large geometric blocks of color, as one would expect.

I looked around these galleries in vain for perhaps my favorite work in the collection, Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie – it’s like visiting an old friend when I see it – but it was nowhere to be found. [Spoiler alert: I did eventually find it and it will be featured in Part 2 of this series.]

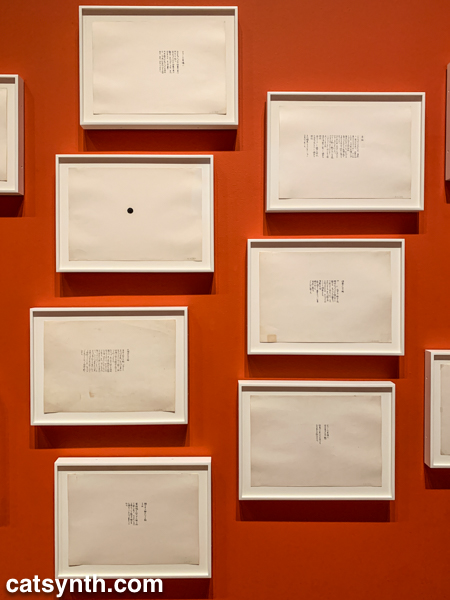

As we move into the late 1950s and the 1960s, abstract expressionism gives way to more conceptual art and works in different media. This was the beginning of Fluxus, with its instructional pieces, happenings, and ephemeral works on cheap materials. There was an entire wall of “scores” for performance works by Yoko Ono. These are always fun – most have clear instructions that one could use to perform them today, though I wonder what was expected from the large black dot.

This is also the era of Nam Jun Paik’s experiments with analog video. Zen for Television takes video art to its most minimal, with a single line of a continuous signal on the screen. However, the vintage television set itself becomes a specific idea when viewed in the 21st century.

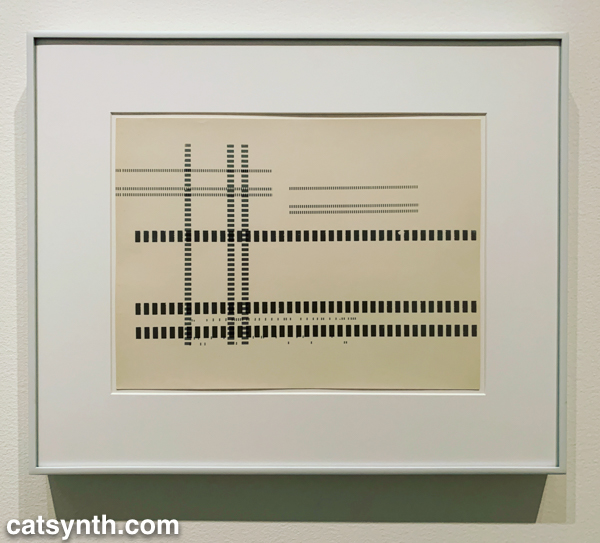

Abstract designs persist in this period, but also take on an industrial and repetitive nature. Sol Lewitt takes this to the extreme, but others Geraldo de Barros left room for variation, and perhaps to the works on paper from Fluxus.

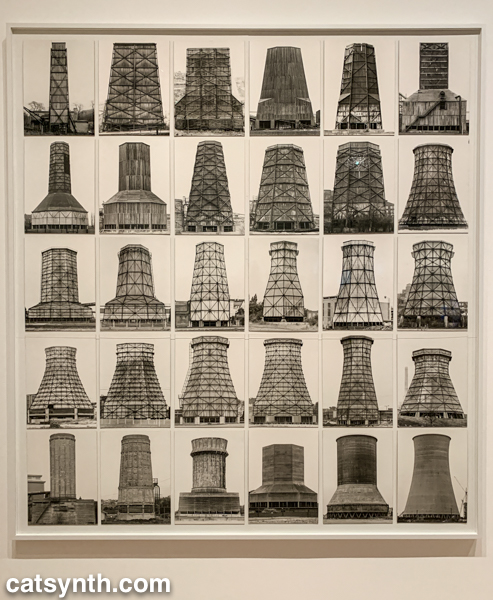

Among my favorite photographers of this period are Hilla and Bernd Becher. There work depicting old industrial buildings and placing them into artistic compositions has been a huge influence on my own photography.

Even after this whirlwind through three floors, seven decades, and multiple exhibits, there was still much of the museum to cover; and I was determined to cover the entirety in one day. In the end, I succeeded, and the remainder of the visit will be covered soon in Part 2 of this series.